Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) is a spectrum of symptoms and signs that present due to actue coronary ischaemia: a blockage of a coronary vessel or vessels. This could be anything from a new onset of angina, to an “ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction”.

History

As with many ED patients this is the key: when did the pain start? what is the character of the pain? did the pain radiate? what were you doing when you got the pain?

Remember that all of these symptoms are as a result of a lack of oxygen getting to the heart muscle – this gives you the “cramping” like pain, with the body’s sympathetic nervous system going into overdrive to try to increase perfusion, resulting in tachycardia, sweating, shortness of breath and a pale complexion as the body redirects blood to try to overcoome the ischaemia.

Patients may have risk factors (such as smoking, family history, diabetes, hypertension and raised cholesterol) but the absence of these does not mean the patient isn’t having ACS (as discussed in this paper1, by St Emlyn’s very own Rick Body).

Examination

Don’t let a College Examiner hear me say this, but often the clinical examination of patient with suspected ACS isn’t that useful. It really is all about the history (and the ECG – but we’ll come on to that in a minute).

You may be able to pick up signs on left ventricular failure (and if accompanied by a systolic murmur this may be very bad news and represent a ruptured mitral valve).

Investigations

The ECG

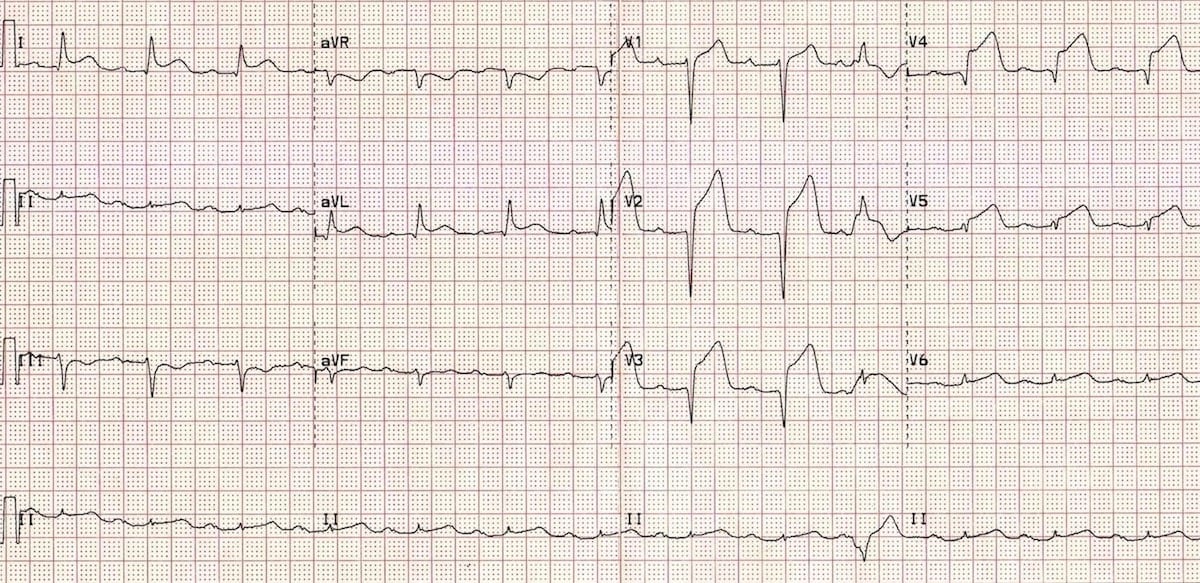

The Electrocardiogram or ECG (or EKG in the US for reasons that I don’t understand) is the key investigation. In fact if you suspect that a patient may have ACS then you should be organising to get this done whilst you continue to take the history.

Signs of an “ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction” should be the first thing you look for2…

Interpretation of ECGs is a skill in itself and there are lots of amazing FOAMed resources available.

High Sensitivy Cardiac Troponin

Troponin (hs-cTn) is a protein that is released when there is damage to the cardiac muscle. This can be caused by a long list of conditions.

It’s name derives from its analytical sensitivity – how good the analysers are at picking up tiny amounts of troponin – but it is also high diagnostically sensitive too. What we mean by this is that the absence of hs-cTn is a good indication that there hasn’t been any myocardial damage. In many EDs as negative hs-cTn test (or tests) may be used as part of a rule out strategy in patients with chest pain.

You can learn loads more about troponin in these blog posts and podcasts.

Treatment

1, Get them to the Cath Lab urgently if appropriate As Emergency Physicians we have one main job with patients who are having STEMI – to facilitate them going for cardiac catheterisation and hopefully angioplasty to unblock the blocked coronary artery.

2, Give them aspirin (unless contraindicated). We have known for some time that the antiplatelet effects of aspirin can increase survival from STEMI (with a number needed to treat in STEMI of 42)3

3, Give oxygen, but only if they are hypoxic. There is no overall survival benefit in giving it to everyone4.

4, Give pain relief if the patient is in pain. This could be in the form of an opiod like morphine, or, if their blood pressure will tolerate it, a coronary vasodilator like GTN (remember the pain is coming from a lack of blood flow and oxygen to areas of the heart so opening these up even a little may help).

Summary

Patients presenting to the Emergency Department with Acute Coronary Syndrome are not uncommon. The key things for the Emergency Physician to do are:

- Concentrate on the history – this is the most important part. Do not be reassured by a lack of “risk factors”.

- Get an ECG and look at it carefully. Practice your ECG interpretation.

- If you are worried at all ask a senior. If the pain is characteristic of cardiac pain or the EGC shows ischaemic changes make things happen so that the patient is considered for cardiac catheterisation as soon as possible.

References

- 1.Body R, McDowell G, Carley S, Mackway-Jones K. Do risk factors for chronic coronary heart disease help diagnose acute myocardial infarction in the Emergency Department? Resuscitation. October 2008:41-45. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.06.009

- 2.Burns E. Anterior Myocardial Infarction. Life in the Fast Lane. https://litfl.com/. Published June 4, 2019. Accessed April 18, 2020.

- 3.Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1988;2(8607):349-360. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2899772.

- 4.Sepehrvand N, James SK, Stub D, Khoshnood A, Ezekowitz JA, Hofmann R. Effects of supplemental oxygen therapy in patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Heart. March 2018:1691-1698. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313089